Large chunks of the planet are still of out of reach of mobile phone signals – billions are still without access to digital communications. But this could change thanks to shrinking satellite sizes and costs.

Lower-cost, space-based mobile phone services will soon be a reality thanks to one firm’s fleet of nano-satellites that will bounce your voice or text signal from one spacecraft to the next and finally down to the person you’re calling.

“People were thinking of using nano-satellites for Earth imagery but nobody had thought of using them for voice or text communications,” says Israeli former fighter pilot Meir Moalem, the chief executive of Sky and Space Global (SAS).

“We were the first.”

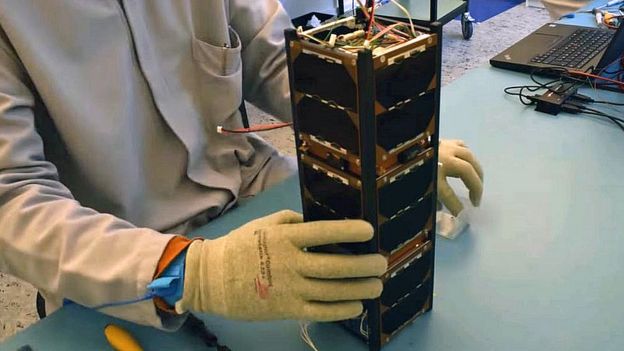

His firm is aiming to offer customers mobile phone connections via a constellation of 200 shoebox-sized satellites weighing just 10kg (22lb) each.

The fleet is set to be operational by 2020 and will provide text, voice and data transfer services to the Earth’s equatorial regions – including much of Latin America and Africa – to a market of up to three billion people.

“Affordable mobile services are critical for the economic and social development of many developing countries,” says Mr Moalem, who believes SAS’s nano-satellites will shake up the space-based communications market.

“Our total constellation costs just $150m (£108m). That’s less than the cost of a single standard communications satellite. This is what we mean when we talk of a disruptive technology.”

But SAS is just one of a number of companies with big plans for space right now.

Perhaps the most ambitious is Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which is aiming to build a huge 4,400-satellite constellation offering global internet coverage. It will be using its own Falcon-9 rockets to launch its fleet and plans to have the network operating by 2024.

SpaceX has ambitious plans of its own for space-based communications

And OneWeb has an 800-satellite constellation set for 2020, again focused on global broadband, while Google and Samsung are also mulling similar initiatives.

With all these satellites, low-Earth orbit – an altitude of 2,000km (1,200 miles) or less above the planet – is becoming an increasingly crowded space. This could make future launches potentially difficult and dangerous with space debris.

Then there is the issue of finance. Not every planned constellation is going to find the investors with deep enough pockets to back it, though David Fraser, research director at APP Securities, says SAS could be “an attractive alternative option” given its low capital costs. Vincent Chan, professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, believes that satellite miniaturisation and cheaper launch vehicles mean that the “nano-sat is ready to serve the public”.

Such lower-cost infrastructure could bring much-needed mobile communications to the world’s poorer regions, he says, helping to reduce the digital divide.

But, he adds, SAS’s focus on voice and text services rather than broadband internet, suggests that “the digital divide will be narrower but not disappear”.

For its part, SAS is using a non-traditional method of getting its satellites into orbit. They will be air-launched in batches of 24 by Virgin Orbit, part of Richard Branson’s Virgin group.

Virgin’s modified Boeing 747-400 will fly up to 35,000ft (10,000m), then LauncherOne, a two-stage liquid oxygen-powered expendable rocket, will blast the payload into orbit.

It’s one of a number of air-launch-to-orbit systems under development.

The advantage of launching from an aircraft is that the rocket can be launched in exactly the direction to suit the satellite’s planned orbit. Virgin is planning its first launch later this year, while SAS’s craft will be launched in 2019.

Launch costs will typically be about $12m, much less than a traditional launch, says Virgin. It is “all about helping the small satellite community get into orbit,” says Dan Hart, Virgin Orbit’s president and chief executive.

Such lower-cost launch services will open up space to “a whole host of communications [and] remote sensing applications,” he says.

SAS has already proved that its communications systems works with three pilot satellites, and is now signing deals with partners in Africa and Latin America – including one of the biggest satellite-communications providers in the Americas, Globalsat Group.

Globalsat’s chief executive, Alberto Palacios, says his firm’s current customers – in the mining, energy, defence banking, and government sectors – can afford the costs of traditional satellite phone calls.

But he believes nano-satellites are a game-changer.

“Some customers invest several hundreds of dollars in the hardware for a satellite phone terminal and will pay $50 a month for the service. But if you can offer a solution for half of that – then the price can be compared to conventional mobile phones,” he explains.

SAS says it is going for the gap in the digital marketing between existing satellite communications operators, such as Iridium, Inmarsat and Globalstar, and land-based mobile networks such as Vodafone, Telefonica, Airtel and Safaricom.

It is targeting customers earning less than $8 a day.

In Ghana, the company has just signed a five-year deal with telecoms provider Universal Cyberlinks to help government agricultural projects and public services, including monitoring cocoa production across 5,000 buying centres and checkpoints.

“When you travel outside of a city in Africa, often you lose your phone signal because it is not cost-effective to put up phone masts everywhere. That’s where we come in,” says Mr Moalem.

“In the West, we tend to forget that in many parts of the world people are not concerned about high-speed internet, they want to make simple phone calls, texting or money transfers. It’s a basic need.”

Africa is certainly becoming a key market for mobile services. There were 420 million mobile subscribers in 2016 and by 2020 there will be more than 500 million, around half the population, says industry body GSMA.